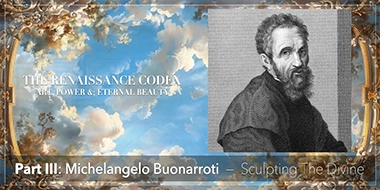

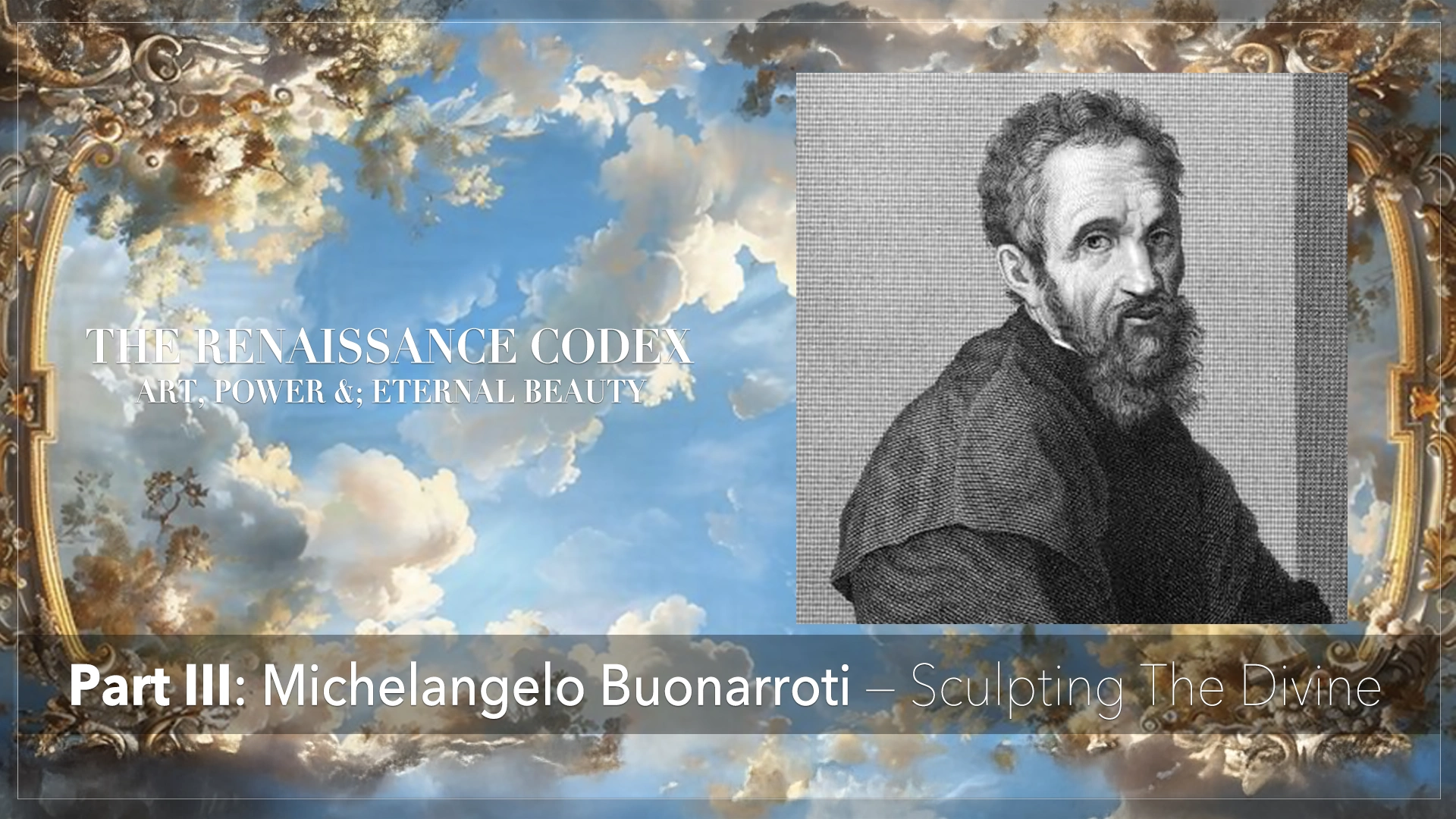

THE RENAISSANCE CODEX

ART, POWER & ETERNAL BEAUTY

Part III: Michelangelo — Sculpting the Divine

ART, POWER AND ETERNAL BEAUTY

- Part I:

Divine Geniuses of the Renaissance - Part II:

Leonardo — The Visionary Beyond Time - Part III:

Michelangelo — Sculpting the Divine -

↳ Part IV:

Raphael — Harmony in Human Form - (UPCOMING NEXT)

↓ - Part V:

Botticelli — Painter of Venus and Dreams - Part VI:

Titian — Fire, Flesh & Venetian Splendour - Part VII:

Echoes of the Renaissance in Modern Luxury

Michelangelo Buonarroti was the hand of the divine given form. More than a sculptor, more than a painter, more than an architect—Michelangelo was a force of nature. To touch stone and summon emotion, to paint a ceiling and elevate heaven—he brought muscular intensity and metaphysical weight to Renaissance art, shaping beauty in its rawest power.

Michelangelo’s work pulses with anatomical precision, forged from his obsession with the body. His statues are not passive—they breathe, mourn, and rise toward transcendence. Every contour is carved with a knowledge of the body that rivalled the greatest physicians. But in his hands, muscle became metaphor.

Madonna of Bruges (1501–1504)

Sculpted in Florence by Michelangelo.

Currently housed in the Church of Our Lady (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk), Bruges, Belgium.

Towering over five meters, David transcends his biblical origins, embodying youth, tension, and readiness. His pre-battle stance radiates anticipation—power in stillness. Much like David’s charged stillness, many modern designers craft garments with architectural precision and sculptural structure—highlighting power, presence, and poised intensity in every fold and cut.

Statue of David

Sculpted by Michelangelo in Florence (1501–1504).

Currently housed in the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence.

The Creation of Adam (1511)

Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

THE RENAISSANCE CODEX

“ART, POWER AND ETERNAL BEAUTY”

The Apotheosis of the Ceiling

Painted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, The Creation of Adam is Michelangelo's most mythic gesture. The near-touching hands between man and God form an eternal arc of yearning, creation, and potential. It is an image that has transcended religion to become iconic in visual culture—from advertising to album art, from fashion designers' campaigns to modern streetwear.

The drama of the human gesture, the sculptural volume of the figures, and the stark contrasts between flesh and void resonate in the sweeping forms of Vera Wang and Dolce & Cabbana, whose aesthetics favour exaggerated silhouettes and architectural cuts. Michelangelo’s ceiling inspired not just awe, but attitude.

In the contemporary imagination, this image is more than sacred—it is stylistic. The sculptural anatomy of the figures, their monumental grace, and the chiaroscuro drama of light and void all find visual kinship in today’s couture. Designers like Vera Wang and Dolce & Gabbana reinterpret Michelangelo’s aesthetic through sweeping silhouettes, nude-toned palettes, and garments that embody tension and release. Their corseted forms, voluminous gowns, and baroque embellishments capture the spiritual theatre of the Sistine ceiling with modern edge and attitude.

In this way, The Creation of Adam, along with the other frescoes, no longer belongs solely to the Vatican. It pulses in the rhythm of the runway and the red carpet, in the symmetry of a silhouette, in the whispered promise of touch. They are living frescoes—rewritten through fashion.

SISTINE CHAPEL

Heaven meets earth in every stroke — Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel

frescoes breathe divine drama, where flesh, fate, and form ascend in sacred splendour.

✦ This ceiling lives on in fashion—its gestures echo in silhouettes, where movement, touch, and divinity become part of the material language.

Marble and Mood

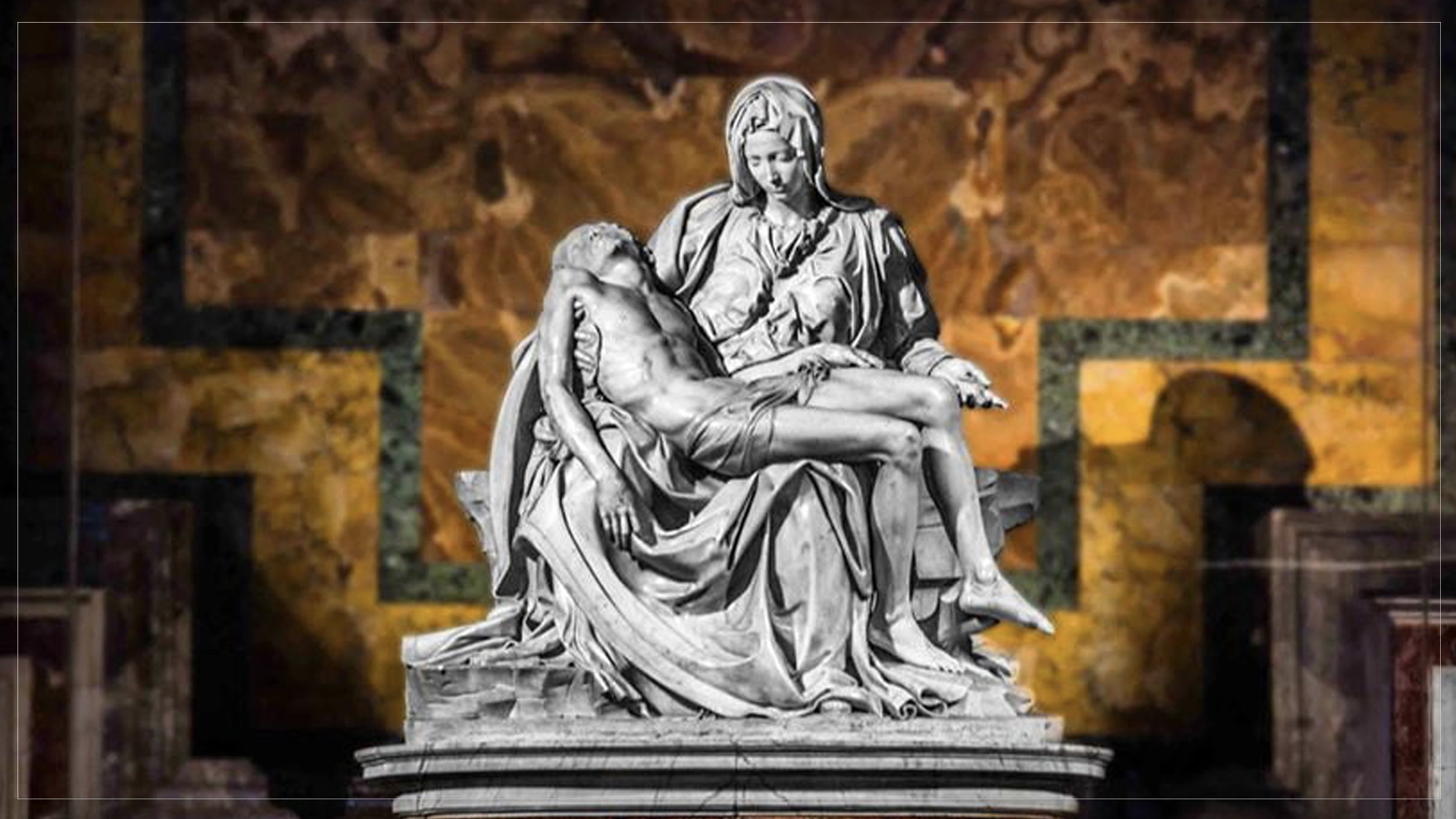

Pietà (1498–1499)

St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

Michelangelo was only 24 when he sculpted the Pietà, a marble requiem of mother and son. Its grief is eternal, carved in smooth curves and silent sorrow. That same tender intensity is echoed in the sculptural folds of Yves Saint Laurent, whose celestial tailoring channels Renaissance restraint with an edge of noir sensuality.

Chanel’s voluminous black cloak evokes baroque drama and sacred ritual, softened by lace and a bold flash of leg—part sculpture, part seduction. Meanwhile, veiled in shadows and Baroque mystery, Dior’s silhouette cloaks the body like a chapel painting come to life, where fabric drapes like a whispered lament.

Michelangelo’s legacy lives not only in museums and cathedrals but also in fashion houses and design studios. His understanding of form and volume, his reverence for anatomy, and his architectural approach to composition continue to shape how we perceive beauty today—whether in Carrara marble or neoprene mesh.

As modern fashion seeks new mythologies, many turn back to the Renaissance for grounding, symbolism, and grandeur. Michelangelo offers with magnificence and with a divine eye for detail.

Saint Laurent

Sculpted shadows and celestial tailoring — Yves Saint Laurent channels Renaissance restraint with an edge of noir sensuality.

Chanel

Renaissance drama reimagined—Chanel’s voluminous cloak and sculpted lace evoke sacred splendour with a whisper of modern seduction.

Dior

Veiled in shadows and Baroque mystery—Dior’s silhouette cloaks the body like a chapel painting come to life.

The Draped Divine

Michelangelo was never bound by his century—his art breathes in the eternal tense. On the contemporary runway, Haute Couturier Stéphane Rolland channels this timeless gravity. His designs echo the sculptural purity of Renaissance forms—draped in architectural folds, carved in light and shadow, they move with the solemn drama of marble come to life. Like Michelangelo’s figures, Rolland’s silhouettes are poised in tension—power held, not flaunted. It is not imitation, but invocation: a dialogue across centuries, where fabric becomes fresco and couture becomes cathedral.

Stéphane Rolland Icons

Next in Part IV: Raphael — Harmony Embodied.

— MeeKar